The much-anticipated follow up to Ling Ma’s post-apocalyptic novel, Severance, Bliss Montage is a collection of eight short stories that aren’t strictly related so much as affectively continuous. Written with straightforward uncanniness that only serves to confound fundamental issues of belonging (but where?), alienation (from whom?) and the ambivalence symptomatic to late-stage capitalism (ubiquitous), it’s not so much a topical departure from Ma’s debut novel as it is a formal one.

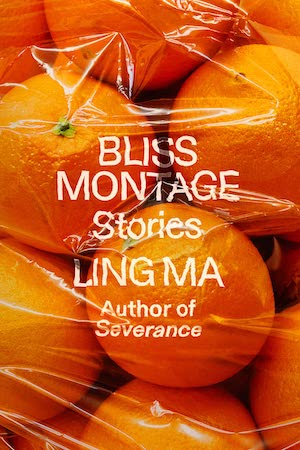

In Severance, Shen Fever, a virus originating in Asia, reduces humans to zombies performing the mindless, most repetitive actions of their capitalist labor. At once disaster text, immigrant biography and millennial bildungsroman, the novel engages a kind of large-scale genre-melding that blurs the boundaries between insidiously imposed narratives (of race, class, plot etc.), and everyday experience. And now in Bliss Montage, this boundary between fabulation and reality is even more thinly-pressed. It’s partly a question of scale. Rather than Severance’s cumulative epic, with its smoothly surreal transitions and turns, Bliss Montage is a series of curtailed snapshots, painting the contours of small lives in broad strokes. Reproductions of crystalline moments, just slightly out of focus. Like the zoomed-in oranges on the book’s cover, submerged under a glaze of plastic, Ma’s stories effortlessly gloss the absurd over the quotidian, holding perfect equilibrium between what is realistic and what’s so bluntly, obviously bizarre as to feel real.

I blasted through this book in a day and couldn’t stop; less a feverish dream state than akin to being buoyed along by a current of shallow, ambient fantasy. Ma’s prose is crisp and lucid, but her stories have a soft, relaxed posture, sifting through direct descriptive information, then perforated by phrases of intense imagistic clarity. A woman is married to a dull finance husband who speaks only in “$$$$$;” their children arrive “one gang-bangingly after the other.” In another story, the water of Miami Beach is a “self-vomiting mass that could be heard but not seen;” a diamond in a wedding ring is “surrounded by glittering micro-spawn.” Less structured than operating according to partially-obfuscated internal logics, there’s a cavalier lack of rationale for the speculative elements of these pieces that’s reminiscent of Izumi Suzuki’s stories in Terminal Boredom.

Buy the Book

Bliss Montage

A fascinating recursiveness happens throughout Bliss Montage, which gathers together characters who are not suffering, nor happy, but not-not-content. They are married; have achieved their normative goals or dream job; are on the precipice of change, whether this is the birth of a child, or a move from New York to the Bay Area. But it’s because of an ever-present feeling of not-rightness that Ma’s protagonists are permeable, enraptured by alternate trajectories, fictive facsimiles and perceived doubles that emerge within their experience. Often, these substitutes allow them to reflect, detached, upon the mechanisms that have motored their lives thus far. But these proxies also tend to bleed, unnoticed, into the protagonists’ senses of self like a virus. Often, they end up flexing the fabric of everyone’s reality. In Oranges, for example, the narrator follows an abusive ex, Adam, to the home of his current girlfriend, Christine. The narrator gets herself reluctantly invited to dinner, then calmly discloses Adam’s violent past. To Christine, her account seems unbelievable, a tall tale. To the narrator, “just looking at [Adam]”—watching him stand in her replacement’s kitchen and offer her pasta, as if she’s an audience member who’s breached the set of milquetoast home sitcom—is confirmation that her abuse really happened. Between the layers of imagination and truth, belief and disbelief, Adam is caught, or created. It’s hard to tell.

In Bliss Montage’s best moments, Ma’s characters feel less like they hold coherent interiorities than they are a series of holograms—their projections and fantasies; desires and fears, made into concrete images that are as tangible as their ‘real’ selves, and passing the reader by at a disarmingly soothing pace. A baby’s arm hangs from a pregnant woman’s crotch, a lover unzips his human suit to reveal what’s decidedly inhuman, a Yeti. Which is not to say that characters have no complexity. In fact, in a late capitalist world, where, Trevor Paglen writes, “[images] no longer simply represent things but actively intervene in everyday life,” where we are compelled to constantly mediate ourselves with images, to become-image in order to be legible to the forms of power that define our relations, Ma’s attention to surface feels paradoxically like a truer quality of depth. “I learned to trust the appearance of things,” one narrator says, in G, a story about two childhood friends who take a drug to render their physical bodies invisible. At first, this is liberating. But soon, the narrator realizes how much of her own individuation is frighteningly contingent on her friend’s ability to look at her—or, to perceive a likeness that’s not-exactly-her, shaped as it is by the intercessions and expectations of their Chinese mothers, who’ve habitually pitted the two girls against each other. “It’s not totally accurate that I felt seen. It was more that: beheld by her, I learned how to become myself. Her interest actualized me,” the narrator says. Later, she becomes permanently invisible, engulfed by her friend’s gaze. There’s a modicum of bisexual relief to it.

If there’s some sly, troubling humor to two Chinese women, who’ve differently defined themselves, assimilating into one single being, it did not escape me. Indeed, in Bliss Montage, discussions of Asian-American identity and race aren’t spared from its radical proposition that perhaps the most accurate representations are not authentic so much as imperfect composites of wavering images. In my favorite story in the collection, Peking Duck, Ma begins with an account from Iron and Silk by Mark Salzman, a foreign language teacher in China who asks his students what the happiest moment of their life is. One student recalls a luxurious meal of roast duck. It turns out that this is not, in fact, his memory, but his wife’s, recounted to him enough times that it’s as if he’s experienced it himself. Resurfacing, unattributed, in a Lydia Davis short story, Salzman’s anecdote is discussed in the narrator’s MFA workshop alongside issues of authorship and appropriation. Then, in that same workshop, the narrator’s own short story, based in her immigrant mother’s real experience, faces an accusation from the only other Asian student in the class that it engages in a form of “Asian minstrelsy.”

If that sounds complicated, it’s because it is. In a stunning feat of multiple meta-displacements, Ma pulls together refracted perspectives to jab at topics like: the white literary imaginary, the role of fantasy in cultural assimilation, the worst parts of MFA culture, and the impasse between immigrant parents and their children. Rather than force a moralizing conclusion in Peking Duck, Ma managed to evoke in me the noncommittal progression of resonance, visceral rejection and fatalistic apathy that doesn’t represent my Chinese diasporic experience so much as reflect how it actually feels. Indeed, it can be difficult to explain to others how my connection to “ancestry” or “homeland” feels based not in what’s correct, per se, but instead in what’s uncertain or irrecoverable, and therefore has to be reconstituted in my imagination. It felt almost spitefully refreshing to read a story that so blithely and incisively toys with diasporic identity—that understands it not as a stable correlation to culture, nationhood or the self, but as a revolving hall of mirrors made up of counterfeited memories, lazy assumptions, petty misgivings and real, unexpected yearning. How all these elements contradict or succeed one another and co-exist, automatically cycling through me like a conveyer belt that will never end.

The truth is, there is something incredibly potent about how Bliss Montage consistently denies us the specific joys of recognition or resolution. Often, the stories end unapologetically—the metaphors left unclarified, the speculative allegories apt, but not directly strung. If characters experience heightened joy or frustration, this tends to find itself suspended in the story, with no outlet for denouement. But it’s exactly because of this that Ma’s critique is clear. We exist in a time of suffering and struggle that is near insurmountable; and yet the streams of capital that flow within us make it difficult to achieve any real impact or emotional catharsis. The point is that despite everything, the montage of our world does not stop. The scroll continues, a sea of images undergirded by power and no longer indistinguishable from life. All we can do is sieve through its textures—and in the rare moments that it cracks or freezes, discover how we’re only gently startled by the tension of being pulled apart; the perfect sensation of hanging ourselves.

Bliss Montage is published by FSG.

Trisha Low is the author of The Compleat Purge (Kenning Editions, 2013) and Socialist Realism (Emily Books, 2019). She lives in the East Bay of California.